Cease and desist letters are not legally binding; they are simply letters asking the recipient to stop doing something. If you believe someone is infringing your intellectual property rights (such as your trade marks, registered or unregistered designs, patents or copyright), sending a cease and desist letter can be a useful way to notify the person of their infringement and ask them to stop.

Cease and desist letters are not legally binding; they are simply letters asking the recipient to stop doing something. If you believe someone is infringing your intellectual property rights (such as your trade marks, registered or unregistered designs, patents or copyright), sending a cease and desist letter can be a useful way to notify the person of their infringement and ask them to stop.

Although a cease and desist letter can’t force the recipient to stop doing anything or to pay you any money, it may encourage them to stop their infringement, be a starting point for negotiation between you and/or be useful as evidence in court that you have taken steps to try to resolve the dispute in good faith.

Cease and desist letter – the basics

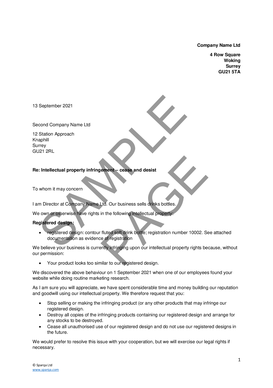

If you believe someone is infringing your IP, the first thing to do is send a cease and desist letter setting out your position and asking the person to stop doing the infringing act. You can find our template cease and desist letter here. For example, you may have discovered that a website’s branding looks identical to yours, or that another company’s product is using the same technology that you have patented.

Our cease and desist letter template sets out who your business is, what intellectual property your business owns, why you believe the recipient is infringing your intellectual property, and what actions you require the recipient to take and by when.

If you are unsure about whether someone is breaching your intellectual property rights, you should seek legal advice (as it is illegal to make unjustified threats in a cease and desist letter). You can access a specialist lawyer in a few simple steps using our Ask a Lawyer service.

Are cease and desist letters legally binding?

Cease and desist letters aren’t legally binding but still have other benefits

No, cease and desist letters aren’t legally binding on the recipient. They have no legal force whatsoever, although you shouldn’t ignore it if you receive one. Even if the letter is written by a lawyer or demands compensation for an alleged IP infringement, it can’t force the recipient to stop doing anything or to pay any money to the sender. However, as set out below, sending a cease and desist letter can still provide benefits.

Reasons for sending a cease and desist letter

Although a cease and desist letter has no legal force, receiving the letter may cause the other party to stop their offending actions, especially if they didn’t know they were infringing on your IP rights. By writing to the person you believe is breaching your intellectual property, you provide them with the opportunity to agree to stop using your intellectual property without resorting to costly and time consuming legal action.

You should write the letter calmly and remain professional. Remember that if you wrongly threaten to sue someone, you can actually open yourself up to being sued. It’s also important to bear in mind that if you do end up going to court over the dispute and lose, the court will take into account your behaviour leading up to the court case when deciding how much money you have to pay the other person.

Letting someone know that a right exists isn’t the same thing as threatening legal action, and a letter is a good way to start off a process which might lead to negotiation, mediation or an agreement, instead of legal action.

If you send a cease and desist letter and this encourages the person infringing your IP to stop, you should get an agreement in writing from them recognising your rights, and stating that they agree to stop. If your competitor starts infringing your rights again after agreeing to stop and you want to take them to court, it may well be easier with this agreement as evidence.

Responding to a cease and desist letter

Always respond calmly and reasonably to a cease and desist letter, and don’t ignore it.

Ignoring a cease and desist letter can encourage the other person to formally take you to court, and potentially may result in you paying more damages because you ignored the original letters.

The way you should respond to a cease and desist letter depends on whether you believe you are infringing the sender’s intellectual property or not.

1. If you aren’t infringing the sender’s IP

A cease and desist letter will describe the acts that the sender claims are infringing their IP rights, such as selling goods using a logo similar to their trade mark. If you know for a fact that you aren’t doing this, you should send a polite but firm letter in reply explaining this. You should try to include some evidence for your claims.

2. If you are infringing the sender’s IP

If you accept that your actions are infringing the sender’s IP rights, you should stop using the sender’s IP. This might involve changing your business name or logo, removing packaging which contains the infringing IP, or stopping sale of infringing products, among other things.

You aren’t legally obliged to pay any money to the sender of a cease and desist letter, but you should politely respond and advise the sender that you’ve stopped the offending actions or that you’ll soon stop. If you do end up going to court over the dispute and lose, the court will consider your behaviour in the run-up to the court case.

Working with the sender may help you avoid court proceedings, for example by signing an agreement confirming that you won’t infringe their IP again. Before signing any legal documents, it’s best to consult a lawyer.

3. If you’re not sure whether you’re infringing the sender’s IP

If you’re unsure whether you’re doing the acts mentioned in the cease and desist letter, or are unsure about whether you should stop those acts, then you should consult a lawyer.

For access to a specialist lawyer in a few simple steps, you can use our Ask a Lawyer service.

The content in this article is up to date at the date of publishing. The information provided is intended only for information purposes, and is not for the purpose of providing legal advice. Sparqa Legal’s Terms of Use apply.

Marion joined Sparqa Legal as a Senior Legal Editor in 2018. She previously worked as a corporate/commercial lawyer for five years at one of New Zealand’s leading law firms, Kensington Swan (now Dentons Kensington Swan), and as an in-house legal consultant for a UK tech company. Marion regularly writes for Sparqa’s blog, contributing across its commercial, IP and health and safety law content.